Krampus, history and tradition

Origins

In German-speaking areas, the Krampus are devils who accompany Nikolaus (a folk figure derived from St. Nicholas of Myra) in the traditional parade along the country’s streets (Krampuslauf). In folklore, Krampus is a horned and anthropomorphic figure described as “half-goat, half-devil”, which during the Christmas holidays punishes the “bad”, unlike St. Nicholas, who rewards the “good” with gifts.

This tradition is now linked to Christian mythology, more precisely to Bishop St. Nicholas and his servant Krampus (sometimes also known as David the Count or in central German areas such as Knecht Ruprecht or “Ruprecht the Servant”). The origins are however linked to pre-Christian pagan cults.

It is a typical holiday event born more than 500 years ago and is still celebrated in Austria, Bavaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia and Northern Italy.

Appearance

The Krampus are unhappy and very disturbing men-of-a-bitch who roam the streets in search of “bad” children. Even though there is a large variety, most share some common features.

The Krampus are hairy, usually brown, black, white or gray, and have the skirts and horns of a goat. They carry chains, designed to symbolize the bond with the devil of the Christian Church accompanied by bells of various sizes. Their faces are diabolical and scary in many variants.

They use ruthenium, birch branch beams that the Krampus use to frustrate the people they meet. Birch branches are often replaced by a normal whip in some representations.

Sometimes Krampus appears with a bag or a back-tied basket. Some of the old chronicles mention bad children who are put into these baskets or bags and taken away.

The origin of this custom, which is proudly maintained in many municipalities belonging to the former Austro-Hungarian area, is lost in the night of the times.

Pagan Origins

The origin of Krampus’s figure is not clear; some folklorists and anthropologists have theorized its origin in pre-Christian times. According to what was published in 1958 by Maurice Bruce, journalist and anthropologist:

“There is no doubt about his true identity of Krampus, no other tradition is found with a legally bound Hindu God. Ruth (the birch whip), apart from its phallic significance, may have a connection with pagan initiation rites; which involved ties and scourges as a form of death. Chains could have been introduced in a Christian attempt to “tie the devil”, but could also be a remnant of pagan initiation rites.”

In the same topic in 1975 the prestigious John Wiley & Sons academic publishing house published an anthropological study by John J. Honigmann

“The San Nicola holiday we describe incorporates cultural elements widely distributed in Europe, in some cases dating back to pre-Christian times. St. Nicholas himself became popular in Germany around the eleventh century, while masks of “devils” acting aggressively and bothering people are known in Germany at least since the 6th century while masks combining the scary with the comic (schauriglustig) became popular in the Middle Ages. The Austrian communities we have studied are well aware of the “pagan” elements blended with the Christian elements of St. Nicholas Day and other traditional winter ceremonies. I believe the Krampus derive from the reverence of a pagan god, who has been assimilated to the Christian devil.”

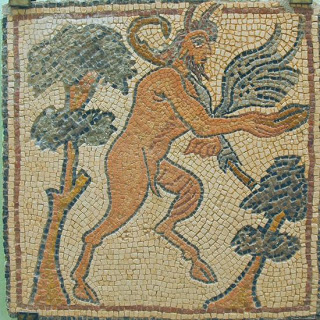

It is plausible that the god pagan to which Honigmann refers is Cernunnos, whose oldest image lies between the rock engravings of Val Camonica, and dates back to the 4th century BC. Another pre-Roman divinity could be Vidadus, venerated in the area of today’s Bosnia.

The figure of these gods was then easily romanized and identified with God Silvanus.

Vidadus, mosaic of the year 540

God Cernunnos, sculptured in Paris around the year zero

Postcard from the late 1800s of a Krampus with a birch Rutren.

Silvanus god, worshipped in the Roman phanteon and often equated with other pre-Roman deities

Cult of God Silvano

Silvanus (from Latin Silvanus) is a figure of Roman mythology, the god of the woods and the countryside, the divinity of nature protection and agresti’s activities. Like the ancient divinities of wildlife, it was considered dreadful and dangerous for newborns and offspring. Deductively and venerated by the peasants, it was the use to appease the god before dissecting a land, with a triple ceremony calling for protection on the pastures, dwellings and soils.

One of the few things you are aware of is that God’s worship was linked to the winter solstice and that his worship was banned from women. The appearance was human, but with thighs and legs of goats and horns on the forehead.

In Cortina, on the slopes of Mount Faloria (formerly Mondeciasadió), rising from Fraina to Mandres on the basal wall of the mountain, stands a characteristic engraving on the rock, a squared rectangle that looks like a huge door. It is the Gate of God Silvano, a place of pagan worship and a tourist destination of rank in the nineteenth century, rarely frequented today.

Gate of God Silvano, on Mount Faloria

Christianization

The figures of Krampus persisted in the Christianization of the population, so in the 16th century the Krampus were definitely incorporated into Christian winter celebrations. The countries of the former Empire of the Habsburgs have largely borrowed the tradition of the Krampus accompanying St. Nicholas on December 6th by the Austrian Duchy, leaving it entirely from the original solstice of winter.

To make sense of the Christianization of a pagan worship so far from the Catholic liturgy, the church invented a legend from nothing:

It is said that in times of famine, young people in the small mountainous villages disguised themselves using furs made of feathers and hides and horns of animals. Being so unrecognizable, they were tempted to terrorize the inhabitants of the nearby villages, robbing them of the supplies needed for the winter season. After a while, however, the young people realized that there was an impostor among themselves: he was the devil himself, who, taking advantage of his real evil face, had entered into the group, remaining recognizable only by the formatted paws goat’s socket.

So Bishop Nicolò was called to exorcise the disturbing presence. Devilish the devil, all the years, the devil-dressed young people, walked along the streets of the country, no longer to plunder but to bring gifts or to “beat the bad children”, accompanied by the figure of the bishop who had defeated the evil.

Of course, St. Nicholas, originally from Bari and bishop of Myra in today’s Turkey, never came to the Alps, but this unlikely legend was enough to “legitimize” the figure of the Krampus.

Krampus in the early 1900s

Right: Russian Icon of St. Nicholas of Bari, Bishop of Myra, of 1294

The feast of St. Nicholas

The feast of St. Nicholas of Bari, bishop of Myra, celebrates of December 6th. The celebration, which mainly takes place in the Alpine region, takes place on the eve of the festival, i.e. on the evening of 5 December. In this case he is remembered as Saint Nicholas and culminates in a parade through the streets of the village. The parade usually follows this order: in the first instance, the same San Nicolò, walking or on a wagon, distributes sweets and sweets to the villagers; to follow the Krampus, a massacade of angry devils armed with whips and chains.

It is curious that masquerading as tradition, and sometimes even in women’s clothing, are exclusively men. But Krampus can also be a female, and in this case it’s called Krampa. Probably also this derives from the exclusion of women from the original pagan cults of Cernunnos/Silvano.

The party begins with bishop San Nicolò who questions the children and shows off with a thick white beard. With children who have behaved well during the year, he will be generous with gifts, including sweet ones, while for those who have not behaved well, there will be a terrible rebuke and charcoal. In addition to this task, San Nicolò must suppress the Krampus anger towards the spectators, sometimes helped by angels.

The Krampus, in fact, show themselves wild, violent and angry. They chase, screaming, screaming and screaming, kids, boys, but also adults and the elderly, push people, whiplashing with birch ruten.

As the sun sets, San Nicolò disappears from the parade, leaving the devils uncontrolled.

Modern history

In Austria after the 1932 elections, Krampus’s tradition was forbidden by the Engelbert Dollfuss regime of the Vaterländische Front and the Christian-Social Party. According to the English Times newspaper, in the 1950s, the Austrian government distributed brochures titled “The Krampus are for evil people.”

Even in northern Italy tradition was persecuted by the Fascist regime, since it was considered too Austrian.

Towards the end of the century there has been and still continues to be a popular revival of celebrations, especially in Tyrol and Bavaria. At the same time, the revival of a local craftsmanship of hand carved wood masks has been seen.

Since 2006, in Austria, the question arises whether Krampus is appropriate or not for children, even coming to propose a ban in Gresten. To date, however, there is no ban on this ancient tradition.